Central Park Sound Walk: Her Long Black Hair

In the study of developmental psychology, one of the first thresholds of an infant’s separation from the mother is crossed once the child finds their own mobility in walking, advancing toward individuation. Even before building command of speech and language, the essential modes of civilized communication, our first physical steps mediate space, not only our orientation under the yoke of gravity, but also relations between self and other. I’ve never considered the act of walking itself as a medium for identity and storytelling through embodied narrative experience. I’ve been on walking tours following the shadow or parasol of tour guides, or even with programmed site-specific narrations on history or art. None of those experiences ever challenged me to navigate the way I mediate the self in negotiation with space and movement until I embarked on Janet Cardiff’s piece, Her Long Black Hair.

As a native of the Upper East Side, the sights and sounds of Central Park are painfully familiar to me. In fact, I’ve been a jaded New Yorker for so long that I often characterize my experience of walking through this city as that of a curator through a museum of my own life. To that end, I am reminded of one of my favorite country songs, “The Grand Tour” sung by the legendary George Jones. The song itself is a guided tour of a tragically broken home, and for each chair he points out or room he croons the listener through, he details accounts of happier times before his wife mercilessly left him and took their child with her. The song ends with the same lyric that opened it, an invitation to “Step right up, come on in…” This ring structure provides a narrative architecture that suggests that this drunken man lives each day in a cycle, trapped on his own tour through memory, love, and loss. I draw this classic country parallel because Her Long Black Hair is a meditation built around a similar emotional mechanic that explores the reconciliation of the internal experiences of heartache and longing with the external experience of space and time.

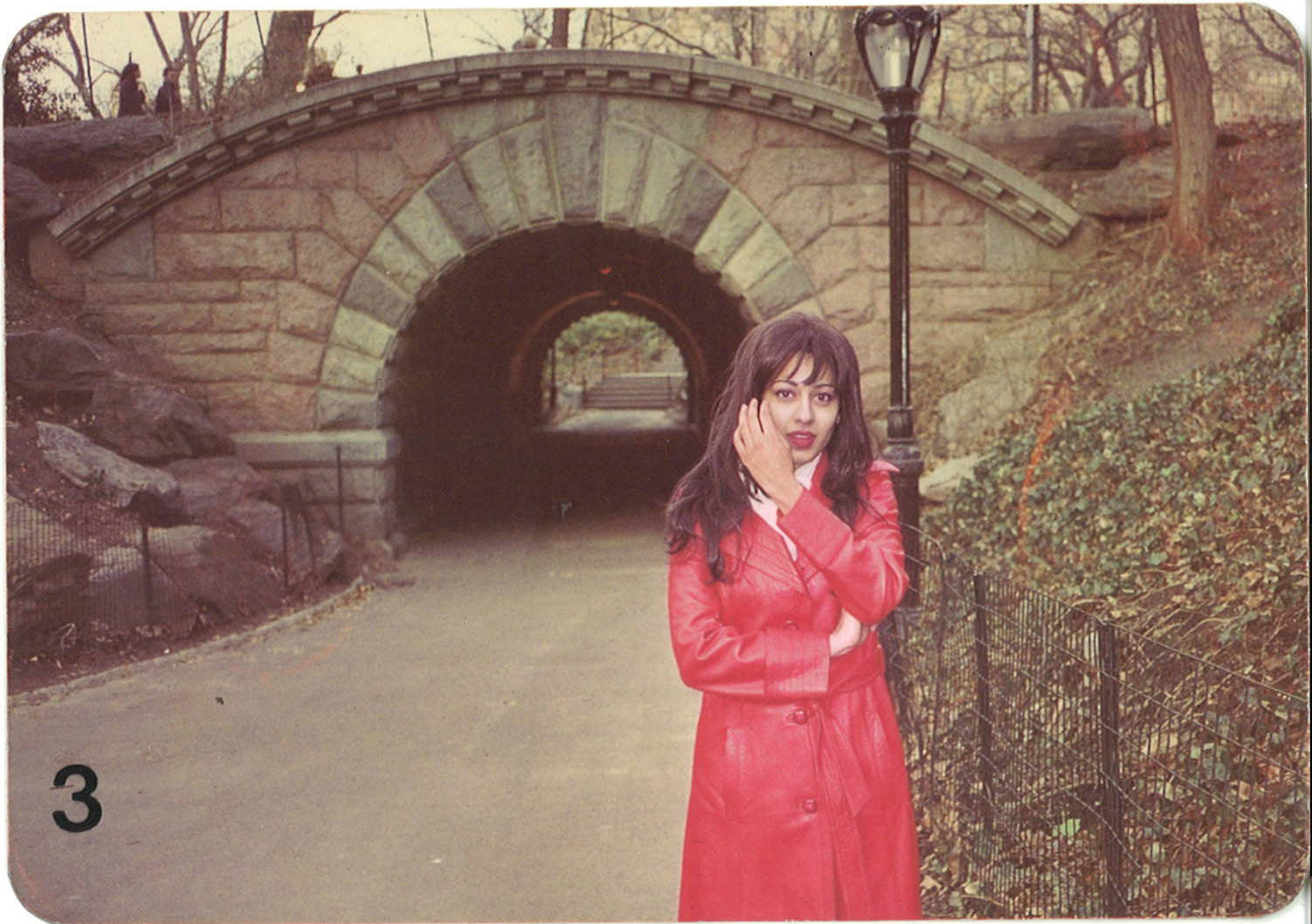

This sound walk was such a beautiful breath of fresh air, enabling me to inhabit my old stomping grounds with a feeling of renewal, restoring in me a perspective of the park with all the magic that never really left the landscape, but had only abandoned me after all these years accreting layers of sediment of my own stories. My body became a moving vessel for this exploration of the memories and sensations of someone else following a vision quest to retrace the steps of either the narrator herself or the mysterious woman in the photographs provided. Are they the same woman? Is this a metanarrative device? I think there is no wrong answer there. I felt that possibly by design, the speaker has displaced the self from versions of herself that trod this path. There was a multiplicity of characters we were tasked with embodying, as she wasn’t just recounting her own memories. Her narration laces her personal introspection through the daily walking habits of European philosophers and theologians while also interweaving passages from diary entries of a fugitive slave on his pilgrimage to freedom. I see this as a procedure intended to juxtapose the dimensions of walking across the divide of intellectual and physical processes: 1) walking as an instrument of traversing intellectual landscapes (internal) 2) walking for survival and toward freedom through the physical world (external) .

The sound walk invited me to excavate the park as a palimpsest, to peel through myself and the “layers in front of my eyes”, to picture the “bones beneath our feet” and the matrixes of space and time that exist, cease to exist, and yet concurrently exist all at the same time. This device positions the park as the quintessential chronotope, a concept coined by literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin that aligns physical space and time as a character both separate and inseparable from history and present as a narrative frame. The narrator describes seeing a man in a t-shirt that reads “Time is an Invention,” and this immersive tour excels at confounding these spatial and temporal boundaries.

Beyond my more speculative theoretical schemata, I was especially moved by the painterly relief with which the pilgrim is tasked to consider the perspective of the architects and landscape designers who built this urban oasis, as well as the manifold ways the listener is instructed to mediate emotions and feelings through all the senses. The sound design enhanced this sensation, augmenting my perspective with the sense that it was raining on a perfectly sunny day, and imbuing my navigation between chaos and refuge. The footfalls of the speaker provide a perfect metronome that I think results in such exactitude of the experiential design, i didn’t stray from our route for a moment.

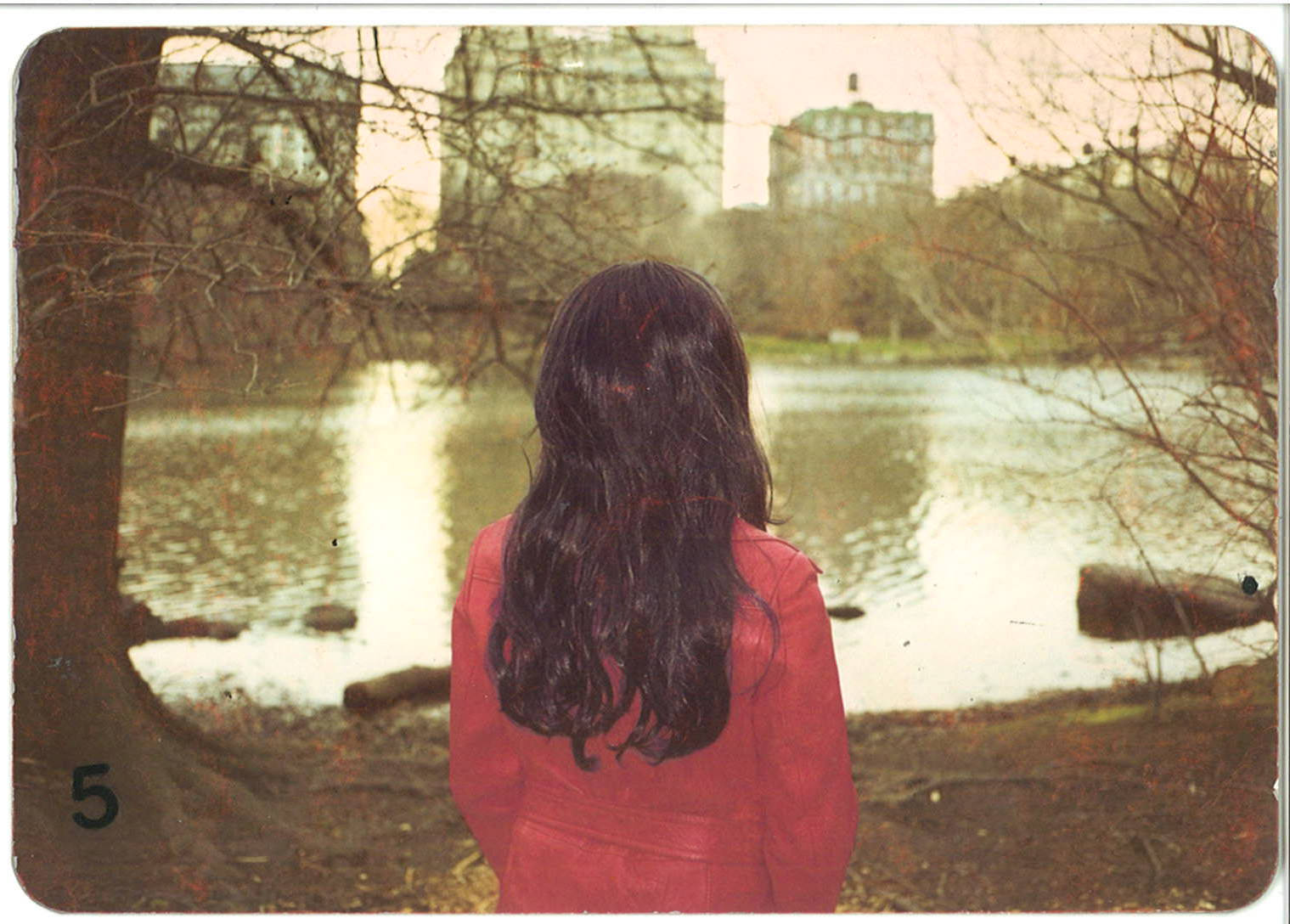

I could write about this for days and weeks. I am tempted to go back and experience it all again, but is that not precisely the warning that lies at the dark core of this piece, the danger of chasing a memory? The challenge of questing through the park sets a bit of a game afoot, to go about matching the photographs with the specific locations of their capture. The multiple allusions to the mythical Orpheus and his ill-fated journey to the underworld suggest that memories can only and perpetually live in the rear-view mirror, that looking back risks a tragedy that can derail even the likes of the ancient hero whose enchanting musical powers can move heavens and earth and even sway the god of death. Orpheus broke the terms of his arrangement and lost his love by falling prey to a temptation to look back, to see if the memory is still there following behind him. Hades’ challenge is a valuable lesson: we must journey on with eyes toward the horizon ahead, we cannot look back lest we violate the memory and lose the self. The final photograph is of the back the woman’s head, her eyes forever fixed upon the waters of oblivion, honoring this silent Orphic vow. The memory cannot look back at us, do we choose to follow it? We know where it leads. Silent and still, and possibly back at the beginning again.